When parents, teachers, or counselors ask, “What’s the most common learning disability in students?” the answer is clear: dyslexia. It affects roughly one in ten school‑age children and shows up early enough that early intervention can make a huge difference.

Understanding Learning Disabilities

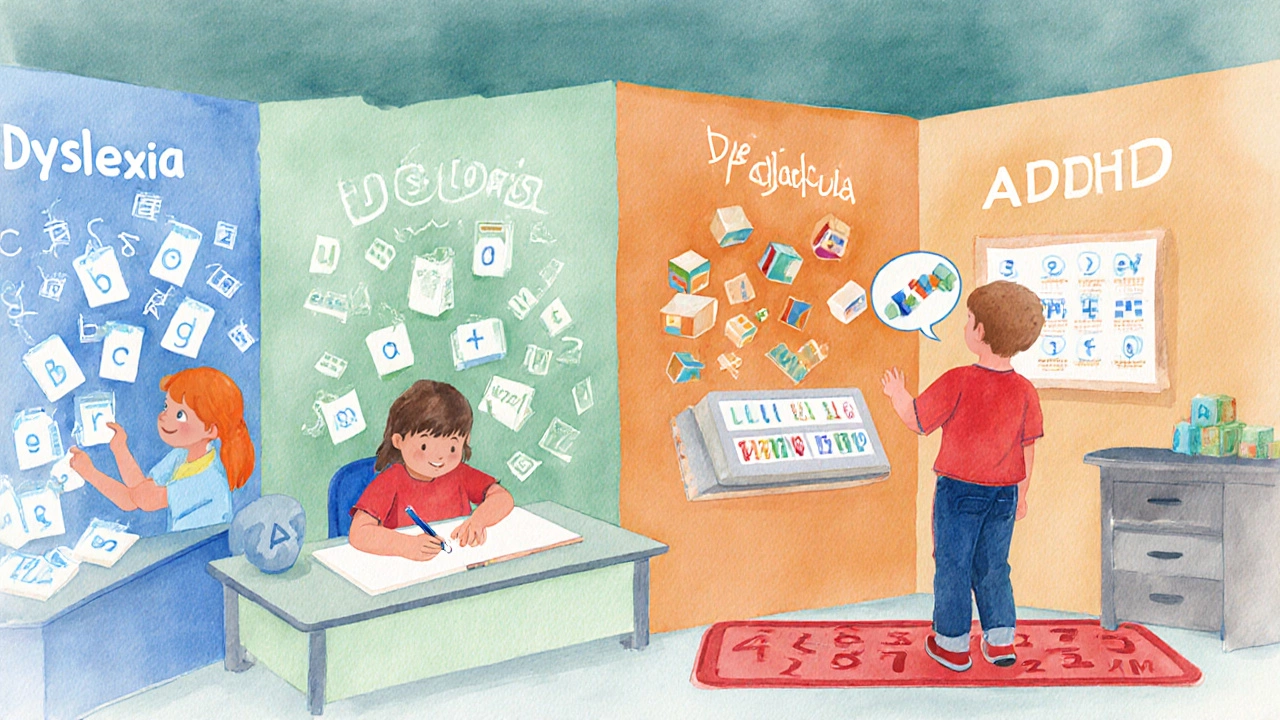

In educational terms, a Specific Learning Disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition that impairs the ability to read, write, or do math despite average or above‑average intelligence. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‑5) groups these under three main presentations: reading (dyslexia), written expression (dysgraphia), and mathematics (dyscalculia). Each has its own profile, but they share common traits such as slow processing speed, difficulty with automaticity, and heightened frustration in academic settings.

What Is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that primarily impairs accurate and fluent word recognition, decoding, and spelling. It stems from differences in how the brain processes phonological information. Studies from the International Dyslexia Association show a prevalence of 5‑10 % worldwide, making it the most frequent learning disability in classrooms across the globe.

Other Common Learning Disabilities

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. While not a learning disability per se, its overlap with academic struggles means many students receive both ADHD and learning‑disability services.

Dysgraphia is a disorder that impairs handwriting, spelling, and the organization of thoughts on paper. It affects roughly 5‑20 % of school‑aged children, often appearing alongside dyslexia.

Dyscalculia is a specific learning disorder that makes understanding numbers, quantities, and mathematical concepts difficult. Estimates place its prevalence at about 3‑6 % of students.

Comparing Prevalence and Core Challenges

| Disability | Estimated Prevalence | Main Academic Impact | Typical Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyslexia | 5‑10 % | Reading fluency, decoding, spelling | Multi‑sensory phonics, Orton‑Gillingham |

| Dysgraphia | 5‑20 % | Handwriting, spelling, organization | Hand‑motor training, graphic organizers |

| Dyscalculia | 3‑6 % | Number sense, calculations, problem‑solving | Concrete manipulatives, visual math tools |

| ADHD (co‑occurring) | 7‑10 % | Attention, time management, task completion | Behavioral strategies, medication, IEP |

Spotting Dyslexia Early

Early signs often appear before formal reading instruction begins. Look for delayed babbling, difficulty rhyming, or trouble learning the alphabet. By first grade, students might struggle with letter‑sound correspondence, read slowly, or make frequent spelling errors despite adequate instruction.

Formal assessment typically involves a multidisciplinary team: a school psychologist conducts cognitive testing, a speech‑language pathologist evaluates phonological awareness, and a special‑education teacher reviews academic performance. Diagnostic criteria require that the reading difficulty persists despite targeted interventions.

Effective Intervention Strategies

Multi-sensory teaching is an instructional approach that engages visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile pathways simultaneously. Research shows it boosts neural connections for decoding and spelling, especially when combined with systematic phonics.

The Orton‑Gillingham approach is a structured, sequential, and multi‑sensory method designed specifically for dyslexic readers. It breaks language into manageable chunks, reinforcing each step through repeated, varied practice.

Schools typically codify support in an Individualized Education Plan is a legally binding document that outlines specific goals, accommodations, and services for a student with a disability. For dyslexia, common accommodations include extended time on tests, audio textbooks, and access to assistive technology like text‑to‑speech software.

A less formal but equally important tool is the 504 Plan is a plan that provides accommodations for students with disabilities who do not require special‑education services under IDEA. Typical 504 accommodations for dyslexic learners might be preferential seating, reduced homework load, or use of a word processor.

Supporting Families and Teachers

Effective communication between home and school is crucial. Parents can reinforce multi‑sensory activities at home-using magnetic letters, singing phonics songs, or apps that highlight letter‑sound links. Teachers benefit from professional development focused on evidence‑based reading instruction, classroom differentiation, and progress‑monitoring tools.

Peer support also helps. Structured reading groups allow students to practice skills in low‑stakes environments, building confidence and reducing stigma.

Common Myths and Pitfalls

Myth: Dyslexia is caused by poor eyesight. Fact: Vision problems can co‑occur, but dyslexia is a language‑processing issue.

Myth: All dyslexic students need the same help. Fact: Dyslexia presents on a spectrum; interventions must be tailored to individual strengths and weaknesses.

Pitfall: Waiting for a formal diagnosis before providing support. Early, universal screening and tier‑1 interventions can prevent widening achievement gaps.

Quick Checklist for Parents and Educators

- Observe early literacy behaviors (rhyming, letter naming).

- Request a comprehensive evaluation if concerns persist beyond kindergarten.

- Implement multi‑sensory, systematic phonics instruction.

- Ensure an IEP or 504 Plan includes realistic goals and accommodations.

- Monitor progress with regular data points (reading fluency, spelling tests).

- Foster a supportive environment-celebrate effort, not just outcomes.

Is dyslexia the same as reading difficulty?

No. Reading difficulty can stem from lack of instruction, language barriers, or other factors. Dyslexia is a neurobiological condition that specifically impairs phonological processing, regardless of instruction quality.

Can dyslexia be cured?

Dyslexia is lifelong, but effective interventions can reduce its impact dramatically. With the right support, most students read at grade level or higher.

How early should a child be screened for dyslexia?

Screening can begin in preschool, focusing on phonological awareness and letter knowledge. Formal assessment is usually recommended by the end of first grade if concerns remain.

What accommodations are most effective for dyslexic students?

Multi-sensory instruction, extended test time, audio textbooks, and assistive technology (e.g., text‑to‑speech) consistently improve outcomes.

Do adults with dyslexia need support?

Absolutely. Workplace accommodations, adult literacy programs, and specialized tutoring can help adults manage reading‑intensive tasks and advance their careers.